Surgery for oral cancer

Surgery is a medical procedure to examine, remove or repair tissue. Surgery, as a treatment for cancer, means removing the tumour or cancerous tissue from your body. If a tumour can be removed by surgery, it is resectable. If it can't be removed by surgery, it is unresectable.

Most people with oral cancer have surgery. The type of surgery you have depends mainly on where the tumour is, the size of the tumour and the stage of the cancer.

Surgery may be the only treatment you have or it may be used along with other cancer treatments. You may have surgery to:

- completely remove the tumour

- remove lymph nodes if the cancer has spread to them or to prevent the cancer from spreading to them

- reduce pain or ease symptoms (called palliative surgery)

- treat cancer that comes back (recurs)

Checking your health before surgery

Your healthcare team will order tests to make sure that you're healthy enough to have surgery and recover from it. Your healthcare team may order the following tests.

Blood chemistry tests see how well your kidneys and liver are working. Find out more about blood chemistry tests.

Lung function tests see how well your lungs are working. Find out more about lung function tests.

Heart function tests make sure that your heart is healthy enough to have surgery. The most common heart function tests done before surgery are electrocardiogram (ECG) and echocardiogram.

A nutrition assessment checks your weight and how well you are eating.

If you smoke tobacco, your healthcare team will encourage you to quit. Smoking can increase the risk of side effects after surgery. It can also increase the risk of cancer coming back (recurring).

Types of surgery for oral cancer

The following types of surgery are commonly used to treat oral cancer.

Wide local excision

A wide local excision removes the tumour along with some normal tissue around it (called the surgical margin).

Doctors mainly use a wide local excision to treat early-stage and locally advanced oral cancer. It may be the only treatment needed for early-stage oral cancer. A wide local excision may also be used to treat oral cancer that has come back.

Glossectomy

A glossectomy removes the tumour and part or all of the tongue.

A

partial glossectomy

is used to treat smaller tumours on the tongue. A small part of the tongue

is removed and the wound is closed with stitches. A skin

A subtotal glossectomy is used to treat larger tumours on the tongue. Because a large part of the tongue gets removed, you will also need to have reconstructive surgery to repair the wound. Reconstruction will help you eat, swallow and speak as well as possible.

A

total glossectomy

removes the entire tongue. This is only done if you have an advanced tumour

(stages 3 or 4). Sometimes, the voice box (larynx) may also be removed

(called a

Mandibulectomy

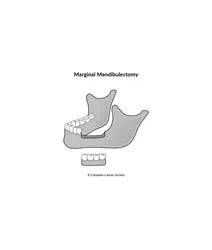

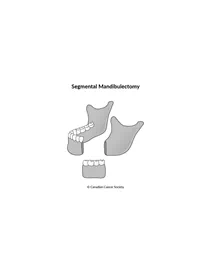

A mandibulectomy removes the tumour and part of the lower jawbone (mandible).

A marginal mandibulectomy (also called a partial-thickness resection) removes only a small piece of bone from the part of the lower jawbone that contains the teeth. It is used when the tumour is close to the lower jawbone but hasn’t grown into the bone or has invaded only the lining covering the bone (called the periosteum).

A segmental mandibulectomy (also called a full-thickness resection) removes a whole section of the lower jawbone. It may be done when the cancer has spread deep into the bone. The removed section of jaw is replaced with a piece of bone from another part of the body. Bone from the lower leg (fibula), hip or shoulder blade can be used in reconstruction.

Neck dissection

A neck dissection removes lymph nodes from the neck. It is often done when cancer has spread to the lymph nodes in the neck or to reduce the risk that the cancer will come back. It is usually done at the same time as surgery to remove the tumour.

You may have lymph nodes removed on one side of the neck (called ipsilateral neck dissection) or both sides of the neck (called bilateral neck dissection).

There are different types of neck dissection. The type of neck dissection done depends on where your doctor thinks the cancer is likely to spread and the size and location of the tumour.

A selective neck dissection removes only the lymph nodes that are most at risk for cancer spread.

A modified radical neck dissection removes most of the lymph nodes on one side of your neck between the jawbone and the collarbone. The muscle, nerves and veins are left in place.

A radical neck dissection removes all of the lymph nodes on one side of your neck as well as muscle, nerves and veins.

In some cases, a sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is offered instead of a neck dissection to check if cancer has spread to the lymph nodes in the neck.

Find out more about neck dissection.

Reconstructive surgery

Surgery to treat oral cancer sometimes damages or removes large portions of the structures in the mouth and jaw. This can affect how you look, speak and swallow.

Reconstructive surgery can repair damage, rebuild structures and restore function in speech and swallowing. It usually involves removing tissue (such as skin, muscle and bone) from another part of the body and using it in the reconstruction. Reconstruction is often done at the same time as surgery to remove the tumour, but it can also be done in a separate surgery.

Your healthcare team will talk to you about what your expectations are before treatment. They will create a reconstruction plan just for you, usually at the same time as they are planning treatment.

Reconstruction will depend on:

- where the tumour is

- your general health and ability to recover from a long surgery

- your personal preference

It can be done using:

- skin from another part of the body (called a skin graft)

- tissue (skin, muscle, bone or a combination of these) from another part of the body (called a flap)

- prosthetics

Skin grafts

A skin graft replaces an area of skin with skin taken from somewhere else on the body. A skin graft can be used to repair small surgical wounds. It can also be used to cover the area where the surgeon removes tissue for a flap. A special instrument called a dermatome removes layers of skin in sheets. The skin is then transferred to the surgical wound.

There are 2 different types of skin graft used for reconstruction of the mouth.

A split-thickness skin graft includes most of the top 2 layers of skin from the donor site: the outer layer of skin (the epidermis) and part of the layer underneath the epidermis (the dermis). Skin is usually taken from the thigh, buttock or upper arm. Skin will grow back in these areas.

A full-thickness skin graft uses the entire epidermis and dermis. Skin is usually taken from the neck, behind the ears or the inner side of the upper arm. The edges of the skin at the donor site are stitched together to close the wound.

Flaps

A regional flap (also called a local flap) is a piece of tissue, sometimes with skin attached, that contains its own blood supply. It is used to repair large surgical wounds. One end of the tissue is cut away from the body, while the other end remains attached to maintain the blood supply. The flap is stretched or moved to the wound site from an area close by and stitched in place.

A free flap is a piece of tissue that has been completely removed from the donor site and is moved to the site needing repair. This requires very careful surgery to connect the tiny blood vessels of the flap to the vessels of the surgical wound. This type of surgery is known as microvascular surgery. Free flaps are commonly taken from the arms, legs, back or abdomen.

Prosthetic facial parts or dental implants

Prosthetic (artificial) facial parts or dental implants are medical devices that replace structures in the mouth that have been removed. They can help with swallowing and speech. Prosthetics can be used to replace the upper jawbone (maxilla) and the front of the roof of the mouth (the hard palate). Dental implants or dentures can be used to replace missing teeth.

Putting a feeding tube in place

You may have surgery to put a feeding tube in place if oral cancer or its treatment affects your ability to swallow. There are different types of feeding tubes that may be used.

Find out more about tube feeding.

Tracheostomy

A tracheostomy makes an opening (a stoma) in the trachea (windpipe) through the neck. A tube (tracheostomy tube or trach tube) is placed through the stoma to create a new path for air to reach the lungs. It's sometimes needed when swelling around the trachea makes it difficult to breathe and is usually temporary. If a tumour is blocking the trachea, you may need a permanent tracheostomy.

Find out more about a tracheostomy.

After oral cancer surgery

Most surgery for oral cancer is done in hospital using a general anesthetic (you will be asleep). How long you stay in the hospital will depend on the type of surgery, your general health and how you feel after the surgery.

When you wake up from surgery, you may have a tube in your neck for breathing (from a tracheostomy). You may also have other tubes, such as tubes for draining fluid or a feeding tube.

You will not be able to eat for a few days after surgery. You will get nutrients through a feeding tube or through an intravenous (IV) tube.

A dietitian will help you with your nutrition needs and guide you on any changes that you have to make to your diet after you leave the hospital. You may also work with a speech-language pathologist (also called a speech therapist) if surgery has affected your speech.

Side effects of surgery

Side effects of surgery will depend mainly on the type of surgery and your overall health. Tell your healthcare team if you have side effects that you think are from surgery. The sooner you tell them of any problems, the sooner they can suggest ways to help you deal with them.

Surgery for oral cancer may cause these side effects:

- pain

- bleeding

- fatigue

- infection

- wound separation (the edges of the wound don't meet together)

- flap failure (there is not enough blood supply and the tissue dies)

- swelling at the surgery site

- lymphedema

- swallowing problems

- difficulty speaking

- chewing problems

- drooling

- difficulty opening the jaw (called trismus)

- weight loss

- nerve damage

- changes in how your lips look and function

-

oral

fistula - scarring

Find out more about surgery

Find out more about surgery and side effects of surgery. To make the decisions that are right for you, ask your healthcare team questions about surgery.

Your trusted source for accurate cancer information

With support from readers like you, we can continue to provide the highest quality cancer information for over 100 types of cancer.

We’re here to ensure easy access to accurate cancer information for you and the millions of people who visit this website every year. But we can’t do it alone.

Every donation helps fund reliable cancer information, compassionate support services and the most promising research. Please give today because every contribution counts. Thank you.