Surgery for brain and spinal cord tumours

Surgery is usually used to treat brain and spinal cord tumours. The type of surgery you have depends mainly on the location and size of the tumour. When planning surgery, your healthcare team will also consider other factors, such as your age, neurological function and overall heath.

Surgery may be done for different reasons. You may have surgery to:

- remove all of the tumour or as much of the tumour as possible

- remove a sample of the tumour to determine the type of tumour

- insert a tube (shunt) to drain cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) to lessen pressure on the brain

- place a device called an Ommaya reservoir to remove CSF or give chemotherapy

- prevent or treat possible complications from the tumour

- reduce pain or ease symptoms

Before surgery

A person with a brain or spinal cord tumour is evaluated very carefully before surgery. The neurological examination looks for any changes to normal functions, such as reflexes, speech, hearing, vision, thinking, movement, feeling and body functions.

The location of the tumour is carefully mapped out before surgery with a series of CT scans or MRI pictures. This will help the surgeon decide if the tumour can be removed with surgery.

Some areas of the brain and spinal cord are difficult to reach or have functions that are too important to be damaged by an attempt to surgically remove the tumour. Tumours that can’t be removed are called inoperable.

The following types of surgery are used to treat brain and spinal cord tumours. You may also have other treatments after surgery.

Craniotomy

A craniotomy is surgery that opens the skull to remove a brain tumour. The goal of surgery is to remove as much of the tumour as possible without destroying important brain tissue or affecting brain functions. You will be under general anesthesia or may be awake for at least part of the surgery if the doctor needs to assess brain function (called mapping).

During the surgery, the surgeon makes a cut (incision) in the scalp. A piece of the skull is removed to expose the area where the brain tumour is growing. This piece of skull is often called the bone flap.

The surgeon then makes a cut in the covering of the brain (dura mater) and pulls it apart slightly to find and reach the tumour.

The surgeon removes as much of the tumour as possible. A special ultrasound machine is sometimes used to break up the tumour and make it easier to remove. The surgeon may also use a special operating microscope that helps to identify the edges of the tumour.

Image-guided surgery may be used for some brain tumours. Images are repeatedly taken with an MRI or a CT scan during the operation to show the location of the tumour and the surgeon’s instruments.

Once the surgeon has removed as much of the tumour as possible, the dura mater is tightly stitched together, the piece of skull is replaced with small screws and plates and the scalp is closed with stitches or staples. If the brain is very swollen after surgery, the piece of skull may be replaced later when the swelling has gone down. Healing usually takes several weeks.

Brain mapping

Brain mapping is done during a craniotomy when a tumour is near areas of the brain that control speech or motor function. Mapping is done with a technique called intraoperative cortical stimulation. It involves stimulating the surface of the brain with a mild electrical current to determine the function of a particular part of the brain. The procedure is painless. It produces temporary speech disturbances or twitching in the part of the body that is controlled by the area of the brain being stimulated. This information is then mapped so that the surgeon can avoid these areas when removing the tumour.

Speech mapping tracks the areas around the tumour that are responsible for speech and understanding speech. After a general anesthetic is given, the surgeon opens the skull and dura mater to expose the brain. You are then woken up so you can talk to the surgeon and follow instructions (such as counting or reading) during the mapping. When the mapping is finished, you are given a general anesthetic again and the surgeon continues the operation to remove the tumour.

Motor mapping tracks the areas around the tumour that are responsible for movement and reflexes. You may remain under general anesthetic. The surgeon stimulates the areas around the tumour with an electrical current and watches for any movement of the body. As with speech mapping, the surgeon uses the mapped areas as a guide when removing the brain tumour.

Surgery to drain cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)

Brain tumours can cause a buildup of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the brain that can cause increased pressure in the skull. This is called intracranial pressure (ICP) or hydrocephalus. It occurs when the tumour blocks the flow of CSF and causes it to build up leading to an increase in intracranial pressure. This can cause headaches, vomiting, irritability and seizures. Surgery to remove the tumour can help with this, but there are also other ways to drain away excess CSF and lower pressure in the skull.

An external ventricular drain (EVD) is a thin tube inserted through the skin and skull into a fluid-filled chamber (ventricle) in the brain. It allows CSF to drain from the brain into a collection system or bag outside the body. An EVD is sometimes used to treat a buildup of CSF before or during surgery to remove a brain tumour. The EVD can’t be left in place permanently so it is replaced with a shunt if drainage is still needed.

A shunt is a narrow, soft, flexible piece of tubing. It has a valve system that regulates the pressure of the CSF and prevents fluid from flowing back into the ventricles. Many shunts have reservoirs that may be used to remove CSF samples. During surgery, the shunt is placed in a ventricle of the brain that is filled with CSF. It leads from the ventricle to the scalp. From there, it runs under the skin of the neck and chest and into the abdominal cavity (not the stomach). The CSF that drains into the abdominal cavity is reabsorbed into the bloodstream. A shunt may be temporary or permanent. It can be placed before or after surgery to remove the tumour.

An endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV) is a procedure in which the surgeon makes an opening and places a tube in the third ventricle of the brain to allow CSF to flow around an obstruction. The surgeon uses an endoscope to navigate within the ventricle and create an internal bypass. ETV is sometimes used to treat a buildup of CSF in the brain. It can also be used to biopsy or remove tumours within the ventricles of the brain.

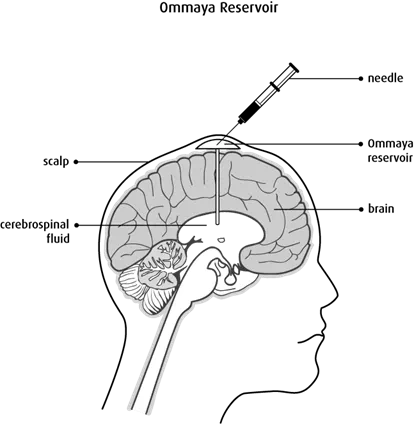

Surgery to place an Ommaya reservoir

An Ommaya reservoir is a small, dome-shaped device with a short tube (catheter) attached to it. The surgeon inserts the reservoir under the scalp and the catheter is threaded into a ventricle in the brain.

The reservoir may be used to remove extra CSF in order to relieve pressure, to get samples of CSF or to inject chemotherapy drugs into the CSF or directly into a tumour.

Laminectomy

A laminectomy is surgery to remove a bone in the spine (vertebra) covering the spinal cord in order to remove a spinal tumour.

During the operation, the surgeon makes a cut in the area of the spine over the tumour and removes the vertebra. The approach is sometimes changed to access the tumour, which may mean removing a rib or accessing the spinal cord through the chest or from behind the abdomen.

The surgeon may make a cut in the covering of the spinal cord (dura mater) to reach the tumour and remove as much of the tumour as possible.

A microsurgical laser may be used to help remove some types of tumours.

An ultrasonic aspirator system, which produces high-frequency sound waves and suction, may be used to break up and remove the tumour.

An u ltrasound may be done during surgery to accurately show the edges of the tumour and confirm that enough bone has been removed to reach the tumour.

When the surgeon has removed as much of the tumour as possible, the dura mater is tightly stitched together so the CSF can’t leak out. The muscles along the spine are also sewn back together.

Adjuvant therapy is started at least 3 to 4 weeks after surgery to give the wound time to heal properly.

En bloc resection

An en bloc resection is a technique in which the surgeon tries to remove the tumour in a single piece. The location of the tumour and how far it extends into surrounding tissue determines the amount of tumour that is removed. En bloc resection is used to remove some spinal cord tumours.

During an en bloc resection, all the tissues (including soft tissue, muscle, ligaments and blood vessels) attached to the vertebra and ribs around the tumour are carefully cut apart.

After all the tissues are separated, the vertebra is detached and removed in one piece along with the entire tumour. Once the tumour is removed, the surgeon rebuilds the vertebra to stabilize the spine.

A marginal en bloc resection removes only the tumour and a wide en bloc resection removes the tumour along with a layer of healthy tissue around the tumour.

During marginal or wide en bloc vertebral body resection, the entire vertebral body is removed. This technique is called a total en bloc spondylectomy (TES). A TES is performed either through both the back and the abdomen or only through the back (posterior-only approach). In the posterior-only approach, the person is placed in a frame and is lying face down.

Stabilization of the spine

When part or all of a vertebra is removed, the spine is weakened. The spine must be reinforced or stabilized so it can function properly.

If the vertebrae above and below the removed section are undamaged, the surgeon can stabilize the spine using fixation devices. These are special pins, plates, rods, hooks or distractible cages (implants that replace a vertebra). The surgeon attaches the fixation devices to the bones above and below where the vertebra was removed.

If there is no stable bone that can be used to attach the fixation devices, the person will remain in bed until a special brace is made and fitted.

Side effects

Side effects can happen with any type of treatment for brain and spinal cord tumours, but everyone’s experience is different. Some people have many side effects. Other people have only a few side effects.

If you develop side effects, they can happen any time during, immediately after or a few days or weeks after surgery. Sometimes late side effects develop months or years after surgery. Most side effects will go away on their own or can be treated, but some may last a long time or become permanent.

Side effects of surgery will depend mainly on the type of surgery, location of the tumour, your age, neurological function and your overall health.

Surgery for brain and spinal cord tumours may cause these side effects:

- bleeding

- infection of the surgical cut (incision)

- pain

- swelling of brain tissue (cerebral edema)

- loss of neurological function

- seizures

- buildup of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the brain

- leakage of CSF through the incision

- increased intracranial pressure

Tell your healthcare team if you have these side effects or others you think might be from surgery. The sooner you tell them of any problems, the sooner they can suggest ways to help you deal with them.

Questions to ask about surgery

Find out more about surgery and side effects of surgery. To make the decisions that are right for you, ask your healthcare team questions about surgery.

Your trusted source for accurate cancer information

With support from readers like you, we can continue to provide the highest quality cancer information for over 100 types of cancer.

We’re here to ensure easy access to accurate cancer information for you and the millions of people who visit this website every year. But we can’t do it alone.

Every donation helps fund reliable cancer information, compassionate support services and the most promising research. Please give today because every contribution counts. Thank you.