Surgery for bladder cancer

Most people with bladder cancer will have surgery. The type of surgery you have

depends mainly on the

Surgery may be done for different reasons. You may have surgery to:

- diagnose bladder cancer and find out the stage

- completely remove the cancer

- remove as much of the cancer as possible before other treatments

- reduce pain or ease symptoms (called palliative surgery)

The following types of surgery are used to treat bladder cancer. You may also have other treatments before or after surgery.

Transurethral resection of bladder tumour (TURBT)

A transurethral resection of bladder tumour (TURBT) removes tumours from the

bladder through the urethra. It is used to diagnose, stage and treat bladder

cancer. It is usually the first surgery done for bladder cancer because it’s the

most common way to

A TURBT may be the only treatment needed for early stages of bladder cancer that haven’t grown into the muscle layer of the bladder wall. Sometimes a second TURBT is done to make sure all the cancer is removed. For bladder cancer that has grown deeper into the bladder wall, a TURBT may be done to remove as much of the cancer as possible before other treatments. This is called bladder-preserving surgery because the bladder is kept in place so you can continue to urinate (pee) normally.

A local, spinal or general

The surgeon burns the area where the tumour was removed with a high-energy electric current (called fulguration) or a laser. This procedure seals off blood vessels and helps destroy any remaining cancer.

A tube (

You may be able to go home on same day as your surgery or you might have to stay in the hospital longer.

Cystectomy

A cystectomy removes all or part of the bladder. It is most commonly done for bladder cancer that has grown into the muscle layer of the bladder wall. Lymph nodes in the pelvis are usually removed (called a pelvic lymph node dissection) following a cystectomy.

Radical cystectomy

A radical cystectomy removes the whole bladder along with surrounding fat and organs. In men, usually the prostate, seminal vesicles and ends of the ureters are removed and sometimes part of the urethra (called a radical cystoprostatectomy). In women, the uterus, cervix, fallopian tubes, ovaries, front wall of the vagina and urethra may be removed (called an anterior pelvic exenteration).

A radical cystectomy is done when the:

- tumour has grown into the muscle layer of the bladder wall

- cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes in the pelvis (lymph node metastases)

- cancer keeps coming back (recurring) after a TURBT and other local treatments, especially when it is high grade

- cancer is in a large part of the bladder

- tumour has grown into nearby tissues or organs outside of the bladder

- cancer is a rare type, such as squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma of the bladder

A radical cystectomy is done using a general anesthetic (you will be

unconscious). The surgeon can do open surgery, making a cut (incision) in

the abdomen to remove the bladder. Or in some cases, the surgeon can do

laparoscopic surgery. For this type of surgery, the surgeon makes several

small cuts and then inserts an

Once the bladder is removed, the surgeon makes a new way to hold urine and pass it out of the body (called urinary diversion).

Partial cystectomy

A partial cystectomy (also called segmental cystectomy) removes only part of the bladder (with the tumour). It is called bladder-preserving surgery because the bladder is kept in place so you can continue to urinate normally. A partial cystectomy is not commonly done for bladder cancer.

A partial cystectomy may be done when:

-

invasive bladder cancer is only in one area of the bladder and the

surgeon can get clean surgical

margins - the tumour is in an abnormal pouch of the bladder wall (called a bladder diverticulum)

- you have urachal cancer (a rare type of bladder cancer)

A partial cystectomy is done using a general anesthetic. The surgeon makes a cut in the abdomen above the bladder. The section of bladder with the tumour is removed along with a margin of healthy bladder tissue around it.

Pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND)

A pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND) is surgery to remove lymph nodes from the pelvis. It is done following a radical cystectomy (or partial cystectomy), usually during the same surgery.

A PLND for bladder cancer is done to:

- remove lymph nodes that contain cancer

- remove lymph nodes that are at high risk of having cancer

- reduce the risk of cancer coming back or spreading

- help your doctor plan treatments after surgery

Find out more about a pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND).

Urinary diversion

A urinary diversion is reconstructive surgery to make a new way for urine to leave the body. It is done after the whole bladder is removed (radical cystectomy). In rare cases, a urinary diversion may be done without removing the bladder to relieve blocked urine flow if the cancer has spread or cannot be removed by surgery.

The type of urinary diversion done depends on many factors, including:

- your age

- how well you can move around

- how well the intestine, liver and kidneys are working

- other medical problems you have

- if you have had radiation therapy

- how close the cancer was to the urethra

- how long you are expected to live (life expectancy)

Urinary diversions can be either incontinent or continent.

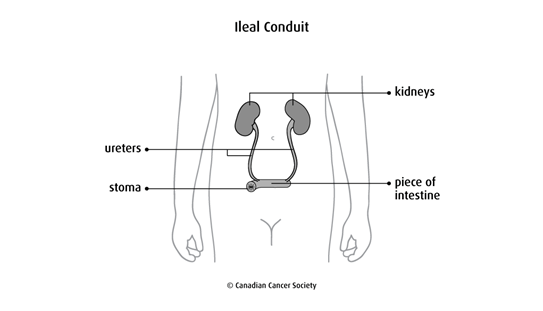

Incontinent diversion

With an incontinent diversion, you don’t control urination. A

An

ileal conduit (also called a loop diversion) is the most common type of urinary diversion

done. The surgeon removes a piece of the small intestine (

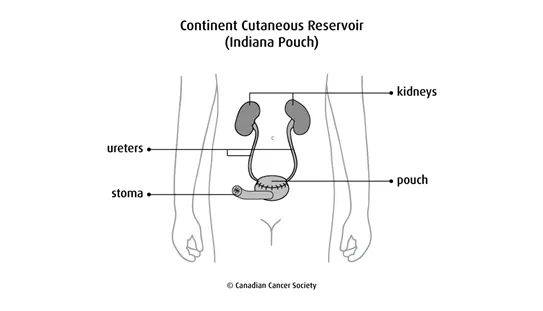

Continent diversion

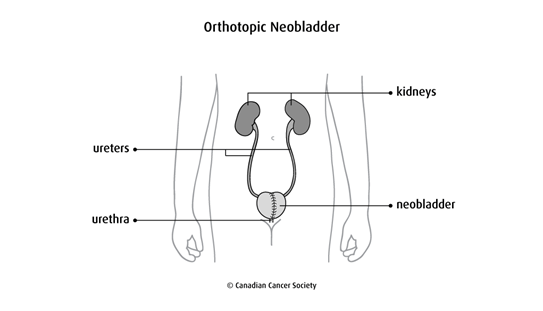

With a continent diversion, you control urination. The surgeon makes a pouch to hold the urine. You drain the urine from this new pouch either with a tube or through the ureter (as you would normally).

A continent cutaneous reservoir (Indiana pouch) is also called a continent

diversion with catheterizable cutaneous stoma. The surgeon creates a pouch

using the right side of the

An orthotopic neobladder is when the surgeon makes a pouch (called a neobladder, or new bladder) usually from part of the small intestine. (Part of the colon may be used in some cases.) The ureters are attached to the pouch, which is then attached to the urethra. You empty the pouch by urinating normally. An orthotopic neobladder is a more difficult type of surgery than other urinary diversions and there is more chance of problems (complications). So it is usually done in younger people without serious medical problems.

Find out more about urinary diversions.

Side effects

Side effects can happen with any type of treatment for bladder cancer, but everyone’s experience is different. Some people have many side effects. Other people have only a few side effects.

If you develop side effects, they can happen any time during, immediately after or a few days or weeks after surgery. Sometimes late side effects develop months or years after surgery. Most side effects will go away on their own or can be treated, but some may last a long time or become permanent.

Side effects of surgery will depend mainly on the type of surgery and your overall health.

A TURBT may cause these side effects:

- bladder spasms, which tend to come and go

- having to urinate often (frequent urination)

- burning when you urinate

- bleeding when you urinate

- urinary incontinence

A cystectomy may cause these side effects:

- pain

- urinary tract infection (UTI)

- urine backs up into the ureters (reflux)

- blocked ureters (obstruction)

- sexual problems for men, such as erectile dysfunction and dry orgasm

- sexual problems for women, such as discomfort or pain during sex

Tell your healthcare team if you have these side effects or others you think might be from surgery. The sooner you tell them of any problems, the sooner they can suggest ways to help you deal with them.

Questions to ask about surgery

Find out more about surgery and side effects of surgery. To make the decisions that are right for you, ask your healthcare team questions about surgery.

Your trusted source for accurate cancer information

With support from readers like you, we can continue to provide the highest quality cancer information for over 100 types of cancer.

We’re here to ensure easy access to accurate cancer information for you and the millions of people who visit this website every year. But we can’t do it alone.

Every donation helps fund reliable cancer information, compassionate support services and the most promising research. Please give today because every contribution counts. Thank you.