Fluid buildup on the lungs (pleural effusion)

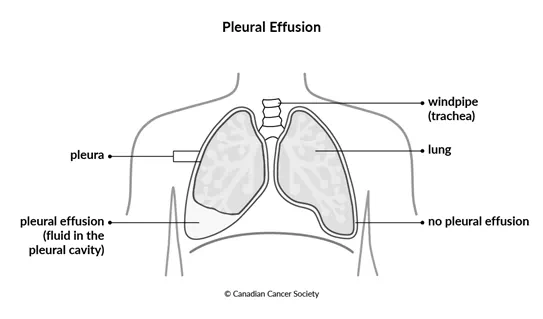

Fluid buildup on the lungs is called pleural effusion. It's when too much fluid builds up in the pleural cavity, which is the space between the lungs and the chest wall. The pleural cavity is surrounded by 2 thin layers of tissue called the pleura that cover the lungs and line the chest wall. Normally there is a small amount of fluid between the layers of the pleura that keeps the tissues moist and helps the lungs breathe without any friction. The fluid is made by cells in the pleura, and it is constantly drained through the lymphatic system and replaced again.

If pleural effusion is a side effect of cancer or there are cancer cells in the fluid, it may be called malignant pleural effusion.

Pleural effusion can be in just one lung or in both lungs.

Causes

Several diseases or medical conditions can cause fluid to build up around the lungs. These include:

- heart failure

- a blood clot in the lung (called a pulmonary embolism)

- liver disease

- a lung infection (pneumonia)

- kidney disease

A malignant pleural effusion is caused by cancer cells spreading to the space between the pleural layers. Cancer cells cause the body to make too much pleural fluid, and they stop the fluid from draining properly. They can also block or change the flow of lymph fluid in the pleural cavity.

The following cancers are more likely to cause pleural effusion:

- lung cancer

- breast cancer

- mesothelioma

- non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- stomach cancer

- kidney cancer

- ovarian cancer

- colon cancer

- cancer of unknown primary

Symptoms

Pleural effusion may not cause any symptoms at first, or the symptoms may be mild. Symptoms of pleural effusion depend on how much fluid there is and how quickly it is collecting in the pleural cavity.

Symptoms of pleural effusion may include:

- shortness of breath

- a cough

- chest pain or a feeling of heaviness in the chest

- anxiety

- a fever (if the fluid becomes infected)

-

malaise

Shortness of breath can get worse when you lie down, which can make it hard for you to sleep. You may get very tired and breathless when you try to exercise.

When you can't breathe very well, you may also be anxious and feel like you are being suffocated.

Diagnosis

Your healthcare team may use the following tests to diagnose pleural effusion:

- a physical exam

- a chest x-ray

- an ultrasound of the chest

- a CT scan

Find out more about these tests and procedures.

Testing pleural fluid

A thoracentesis is a procedure that drains extra fluid from around the lung. A hollow needle is inserted between the ribs into the pleural cavity. The needle is used to remove the fluid.

The fluid removed from the pleural cavity during a thoracentesis is examined in a lab. This fluid can help your healthcare team identify the cause of the pleural effusion. There are 2 types of fluid.

Transudate fluid

is watery and light coloured. It has little or no protein and low levels of

an enzyme called

Exudate fluid is thick and cloudy. It has high levels of protein and LDH. Exudate fluid is most often caused by a lung infection, a pulmonary embolism or cancer. Cancer cells may be found in the fluid. Looking at these cancer cells can help identify the type of cancer causing pleural effusion in people who don't have a history of cancer.

Blood and pus may also be found in the fluid that is removed. If there is blood in the fluid, it is most likely caused by cancer. If there is pus in the fluid, it is caused by a lung infection.

Cell and tissue tests may also be done on the fluid to look for any genetic changes that may help identify the type of cancer or help with treatment decisions.

Find out more about a thoracentesis.

Treating pleural effusion

If you have been diagnosed with pleural effusion but do not have any symptoms, your healthcare team will follow you closely. If you start having symptoms or problems breathing, they will start treatment.

Fluid often builds up again after it is removed, so you may need more than one treatment. You may be offered the following treatment options for pleural effusion.

Draining the fluid

A thoracentesis may be used to drain extra fluid from around the lung. If you have shortness of breath, it will improve as soon as the extra fluid is removed. But the extra fluid may build up again. While a thoracentesis may be done again, it can cause scar tissue and fluid pockets in the pleura, and it can make it harder to remove the fluid if it is done too often.

Tunnel catheter

If fluid keeps building up in the lungs, your healthcare team may offer to place a tunnel catheter so that you can have treatment at home. This procedure is usually done in an outpatient clinic.

A thin, soft silicone tube is placed inside the chest cavity through a

small cut (incision) between the ribs under local

Fluid is drained 2 or 3 times a week by a nurse at home or at a local health unit. When the pleural fluid dries up, the tube is removed.

Chest tube

In the hospital, the doctor or surgeon may place a tube through an incision in the chest between the ribs and into the pleural cavity. The tube is left in place to drain the extra fluid that is causing the pleural effusion.

A chest tube may be placed at the end of a video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). VATS is a type of chest surgery done with a flexible tube (called a thoracoscope) that has a camera attached to the end. The thoracoscope is placed inside the chest cavity through an incision in the ribs. The surgeon uses the camera as a guide to look at the pleural cavity. Then the chest tube is put through the incision and into the pleural cavity where the fluid is collecting. The pleural fluid drains into a bottle at the end of the tube.

Pleurodesis

A pleurodesis is done to stop a pleural effusion from coming back after it has been drained. A pleurodesis seals up the space between the 2 layers of the pleural lining surrounding the lungs. It uses a chemical called a sclerosing agent to irritate and scar the lining so that it sticks to the lung. The most commonly used sclerosing agent is talc.

A pleurodesis is done using a VATS surgery for placing a chest tube after the surgeon has found and drained the pleural effusion. After the fluid has drained, a sclerosing agent is put into the tube, which is closed to keep the agent in the area where the fluid was removed. Once the pleural membrane is sealed, the tube is opened and drained.

You may have to have the procedure done again to completely seal the layers of the pleura to stop the fluid from building up.

Side effects of treatment

Side effects of treatment will depend mainly on the type of surgery and your overall health. Tell your healthcare team if you have side effects that you think are from your chest tube or tunnel catheter. The sooner you tell them of any problems, the sooner they can suggest ways to help you deal with them.

Surgery for pleural effusion may cause these side effects:

- infection

- fever

- pain

- collection of pus in the pleural cavity (called empyema)

- a drainage tube that moves out of place

Cancer treatment

Your healthcare team will treat the cancer that has caused pleural effusion. The treatment you have will depend on the type of cancer. You may receive chemotherapy, targeted therapy, hormone therapy, radiation therapy or a combination of these treatments.

If you have a chest tube or tunnel catheter, the amount of fluid draining from the tube is a good way to tell how well your cancer treatment is working. Talk to your healthcare team about the amount of fluid and what it means.

Medicines

Your healthcare team may prescribe different drugs depending on the causes and symptoms of the pleural effusion.

You may be given antibiotics if you have an infection. You may also be given steroids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to relieve pain and reduce inflammation, or swelling.

Improving breathing

Your healthcare team will suggest treatments to help you breathe easier.

Drugs that relax and widen the airways or tubes in the lungs are called bronchodilators. They can help you get more air into your lungs.

A physiotherapist on your healthcare team will be able to teach you deep breathing exercises that may help with feeling short of breath.

Your healthcare team will also check the oxygen levels in your blood. If you have low levels, you may be given oxygen therapy to make sure you get enough oxygen if you have trouble breathing. You breathe the oxygen in through a mask over your nose and mouth or through tubes in your nostrils.

Your healthcare team may offer opioids, a type of narcotic pain medicine to help with shortness of breath. They are given in much lower doses than those given for pain relief. Opioids can help make you more comfortable.

Your trusted source for accurate cancer information

With support from readers like you, we can continue to provide the highest quality cancer information for over 100 types of cancer.

We’re here to ensure easy access to accurate cancer information for you and the millions of people who visit this website every year. But we can’t do it alone.

Every donation helps fund reliable cancer information, compassionate support services and the most promising research. Please give today because every contribution counts. Thank you.