A diagnosis of eye cancer can come as a shock. “You never think something like eye cancer could happen to you,” says one 54-year-old diagnosed with uveal melanoma, the most common eye tumour in adults. “It was overwhelming, and I had so many questions.”

Eye cancer can be difficult to diagnose. Many eye tumours are benign and, often, the only ways to tell which ones are cancerous are to monitor them for growth or perform a biopsy, which involves removing cells from the tumour or the eye using a needle. Doctors prefer to do this only when necessary because it can be hard to get a sample of the tumour without damaging the eye or spreading the cancer – and even successful biopsies can be painful or invasive for the people receiving them.

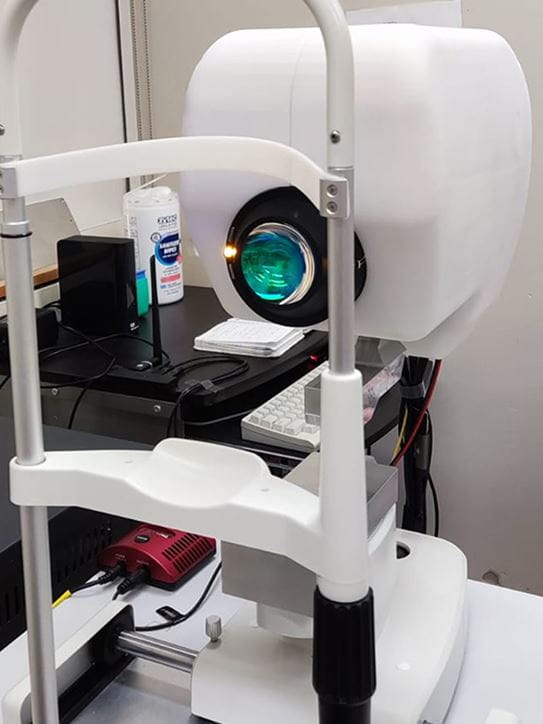

To give people an alternative, Dr Zaid Mammo and his team at the University of British Columbia have used a CCS Challenge Grant to develop a new form of eye imaging called polarization-diversity optical coherence tomography (PD-OCT). These scans seek to identify cancerous tumours in the eye and even spot benign tumours that show signs of turning into cancer.

“This technology helps doctors see what’s happening inside the eye in much more detail without needing surgery,” explains the patient, whose cancer has been monitored using PD-OCT. “That means they can catch problems earlier and treat them before things get worse.”

Uveal melanoma is a serious diagnosis – and its prognosis hasn’t changed much in over 50 years. That’s why support for studies like these is so important. “CCS funding allowed us to build the prototype, validate it in clinical settings and support the research team to push the technology forward,” says Dr Mammo. “Every dollar helps bring us closer to a real-world impact for patients.”

Now, the researchers are testing how well it performs in their clinic, hoping to bring it to clinics across Canada. “Our pilot studies have shown promising potential to distinguish changes within recurrent melanoma that were not reported before,” says Dr Mammo. “We hope to be able to use these changes in diagnosing patients with suspicious lesions.”

Dr Katherine Paton, head of the ocular oncology service at the Eye Care Centre in Vancouver, is already using Dr Mammo’s system. Instead of waiting to see eye tumours grow over time, the technique could allow doctors like her to diagnose and treat eye cancer early and non-invasively. “There will be fewer metastases and improved long-term survival if cancers are identified early,” she explains.

But research is vital to continuing this progress. “Innovations like PD-OCT won’t happen without investment in niche, high-impact research,” says Dr Paton. “Funding helps us move from clinical suspicion to precise, real-time diagnostics that save sight and lives.”

Help fund world-leading cancer research

With almost half of all Canadians expected to face a cancer diagnosis in their lifetime, the urgency for funding is at an all-time high. Research holds the key to transforming the future of cancer.

If everyone reading this joins our monthly donor community today, we can keep up the momentum for life-changing discoveries to better detect, diagnose and treat all types of cancer.

Please donate today because every contribution counts.