Eye problems

Eye problems can develop during and after some types of cancer treatment. Sometimes eye problems happen as a late effect of treatments for cancer during childhood.

How the eyes work

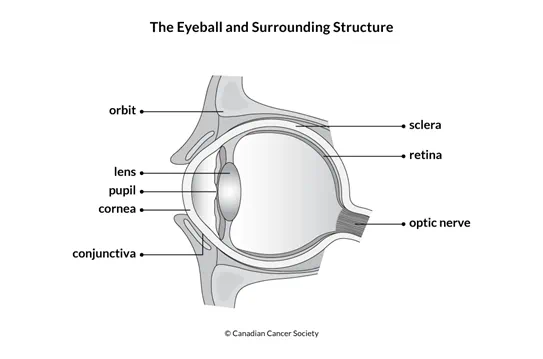

The eye is located in the orbit (eye socket) of the skull. The eyes work with the brain to let you see. Each eye works much like a camera. It collects light, turns it into electric signals and sends those signals to the brain.

Light enters the eye through the cornea. The cornea then bends and focuses the light through the pupil. The pupil controls how much light enters the eye. The lens is behind the pupil and focuses the light on the retina. Nerve cells in the retina change the light into electrical impulses and send them through the optic nerve to the brain. The brain then turns the signals into a visual image or picture for you to see. You have 2 eyes, so 2 pictures are usually created. If you lose the vision in one eye, you can still see most of what we could see before.

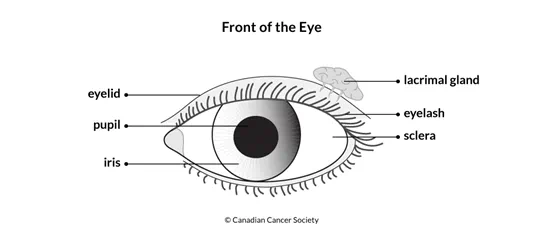

Tears are made in the lacrimal gland. Tears lubricate the conjunctiva covering the surface of the eye and inner eyelid. Tears also remove dust and debris from the eye and help prevent infection. Small ducts drain tears from the eye through very tiny openings inside the inner corner of the eyelid.

Causes

The following can cause eye problems during or after cancer treatment.

Radiation therapy

Radiation given directly to the eye (orbital radiation), to the entire body (total body irradiation, or TBI) or to the brain (cranial radiation) can cause eye problems. Even low doses of radiation can increase the risk of eye problems, such as:

- xerophthalmia (dry eyes)

- sicca syndrome (gritty eyes)

- photophobia (light sensitivity)

- lacrimal duct atrophy (watery eyes)

- orbital hypoplasia (changes to the shape or size of the eye socket)

- blindness in one or both eyes

- double vision

- cataracts

Radioactive iodine for thyroid cancer can cause watery eyes.

Chemotherapy and other drug therapy

Drugs that cross the blood-brain barrier can cause changes in the eye and how it works. Children who are younger than 12 years of age when treated with these drugs can have more serious eye problems than people who receive them when they are older.

Certain chemotherapy drugs, such as busulfan, cisplatin, ifosphamide, methotrexate and vincristine, can cause late effects including cataracts, dry eye syndrome and impaired vision.

Corticosteroids, such as prednisone and dexamethasone, can also increase the risk for cataracts. Recent research reports that inhaled steroids may cause high pressure in the eye or increase the risk for glaucoma. Immunotherapy drugs, such as imatinib, can cause swelling around the eyes.

Some chemotherapy drugs, such as dactinomycin (Cosmegen) and doxorubicin, can increase the risk for eye problems if they are given with radiation therapy.

Surgery

Having surgery to remove a tumour in or close to the eye can increase the risk for eye problems.

Stem cell transplant

Dry eyes are very common in people who develop chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) after a stem cell transplant. People who have received an allogenic stem cell transplant and TBI have a greater risk for cataracts. Long-term treatment of GVHD with high doses of steroids is also thought to increase the chance of developing cataracts.

Brain tumour

Tumours that develop in certain areas of the brain can put pressure on the optic nerve and cause eye problems. Other problems related to brain tumours can sometimes affect the eyes and the ability to see. These problems include increased intracranial pressure, increased collection of fluid (hydrocephalus) or blockage of a shunt or drain.

Other factors

The following factors can increase the risk for eye problems:

- Diabetes increases the risk for problems involving the retina and optic nerve.

- High blood pressure increases the risk for optic chiasm neuropathy (damage to the nerve that sends messages from the eye to the brain).

- Frequent exposure to sunlight increases the risk for cataracts.

Types of eye problems

Different eye problems can develop after cancer treatment, including:

Blepharitis is inflammation of the eyelids.

Cataracts are when the lens of the eye becomes clouded so light can't pass through it easily. This can cause blurred, double or faded vision. Some chemotherapy drugs, biological therapies, steroids and the hormone therapy tamoxifen can increase the risk for cataracts.

Enophthalmos is when the eyeball is sunken in the orbit due to radiation therapy.

Glaucoma is increased pressure in the eye. It is a very serious condition. It can damage the optic nerve and cause vision loss. Glaucoma can sometimes occur after treatment of eye cancer.

Keratoconjunctivitis sicca is inflammation of the cornea and the conjunctiva due to dryness. It is commonly known as dry eye syndrome. It happens when radiation or GVHD lessens the amount of tears produced by the lacrimal gland. This causes pain and light sensitivity.

Lacrimal duct atrophy is shrinking of the lacrimal duct, which causes more tearing or watery eyes. It can be caused by radiation to the eye or orbit or by radioactive iodine treatment for thyroid cancer.

Maculopathy is damage to the macula (middle part of the retina) causing blurred vision. Certain chemotherapy drugs or radiation therapy increase the risk of maculopathy.

Optic chiasm neuropathy is damage to the nerves that send messages from the eye to the brain. This can cause vision loss. Certain chemotherapy drugs or radiation therapy can increase the risk of optic chiasm neuropathy.

Orbital hypoplasia is when the eye and surrounding tissue don't develop properly, causing a small eye or orbit. It can be caused by radiation to the eye or orbit in young children.

Papillopathy is swelling of the area where the optic nerve enters the eye. This can happen after radiation therapy to the eye.

Photophobia is when the eyes are sensitive to light. Drugs that may cause photophobia include cytarabine, fluorouracil, tretinoin and drugs used for photodynamic therapy (PDT).

Retinopathy is damage to the retina causing vision loss.

Telangiectasias are enlarged blood vessels in the sclera (white part of the eye).

Xerophthalmia is dry eyes due to scarring of the lacrimal glands, which make tears. It can be caused by radiation to the eye or orbit or by chronic GVHD from a stem cell transplant.

Symptoms

Symptoms can vary depending on the type of eye problem and include:

- not being able to see objects that are close

- not being able to see objects that are far away

- double, cloudy or blurred vision

- seeing faded colours

- seeing halos or rainbow-like rings around lights

- poor night vision

- being sensitive to light

- loss of vision or loss of areas of vision

- headaches

- dry, itchy or burning eyes

- swelling

- the feeling that there is something in the eye

- watery eyes

- pain

- redness

- sclera that doesn't look white

- lumps or tumours on the eyelid

- a drooping eyelid

- a small eye and orbit

- a sunken eye

- nausea

If symptoms get worse or don't go away, report them to your doctor or healthcare team without waiting for your next scheduled appointment.

Diagnosis

You may see an eye specialist, such as an ophthalmologist or optometrist, to check your eye problem. Regular eye monitoring is important, especially if you:

- had radiation therapy to the head, brain or eyes

- had TBI for a stem cell transplant

- had a tumour in or close to the eye

- have GVHD from a stem cell transplant

Eye problems are usually diagnosed by an eye exam. During an eye exam, the doctor will:

- put drops in the eyes to dilate the pupils

- use an instrument that shines a narrow beam of light in the eye (called a slit-lamp exam)

- look at the inside of the eye, including the retina and the optic nerve

- take pictures of the eye to keep track of changes in the eye

The ophthalmologist will also examine the inside of the back of the eye using a magnifying lens and light.

Managing eye problems

Once the extent and cause of an eye problem is known, the healthcare team can develop a treatment plan. Not all eye problems need to be treated right away or at all.

If vision problems develop, it is important to follow the treatment recommendations of the ophthalmologist. If vision problems are permanent, you will be referred to services in the community to help people with vision impairment.

Blepharitis is mainly treated with regular cleaning of the eyelids.

Cataracts may not need treatment. Your ophthalmologist will monitor your vision closely and recommend treatment when it is needed. Cataracts are treated with surgery to remove the lens and replace it with an artificial one.

Enophthalmos may be treated with plastic surgery to build up the eye socket.

Glaucoma may be treated with eye drops, medicines, laser treatment or surgery to lower the pressure in the eye.

Keratoconjunctivitis sicca may be treated with artificial tears or ointments to moisten the eye. If it is caused by an infection, your doctor will prescribe antibiotic eye drops or ointment. Your doctor may also suggest wearing a patch over the affected eye while you sleep to help with healing. In rare cases, surgery may be done to replace the cornea (called a cornea transplant).

Lacrimal duct atrophy may be managed with medicines or warm compresses to reduce swelling, if that is the problem. If heavy tearing can't be managed, surgery may be done to widen the tear drainage system.

Maculopathy and retinopathy may be treated by applying a laser or heat to the retina. In rare and severe cases, surgery is done to remove the eye.

Optic chiasm neuropathy has no current treatments.

Orbital hypoplasia usually isn't treated. In severe cases, the doctor may rebuild the bones around the eye.

Papillopathy may be treated with medicines.

Photophobia may be treated using steroid eye drops. It can also help to wear sunglasses to lower the amount of light your eyes are exposed to.

Telangiectasias doesn't need treatment.

Xerophthalmia can be treated with artificial tears (eye drops) or ointments to moisten the eye. In severe cases, surgery may be done to block the tear drainage system so that tears aren't drained from the eye too quickly.

Protecting your eyes

Some treatments for cancer put you at higher risk of developing eye problems. You can protect your eyes by doing the following:

- Wear sunglasses with UV protection.

- Use protective eyewear when playing sports, mowing the lawn or doing anything that may get particles or fumes in your eyes.

- Be careful when using hazardous chemicals at home or work.

- Avoid accidents by not playing with things that have sharp parts or parts that stick out and not using fireworks or sparklers.

See your doctor right away if you injure your eye.

Follow-up

All people who are treated for cancer need regular follow-up. The healthcare team will develop a follow-up plan based on the type of cancer, how it was treated and your needs.

If you develop vision problems, you should be seen regularly by an ophthalmologist.

If you have had any of the following, you should have an eye exam by an ophthalmologist at least once a year:

- treatment for a tumour of the eye

- radiation therapy to the eye, orbit or brain

- GVHD as a result of a stem cell transplant

If you received radioactive iodine treatment and have too much tearing, you should see an ophthalmologist.

If you have an artificial eye, you should see an ocularist (a person who makes and fits artificial eyes) at least once a year.